530 Million Years Ago

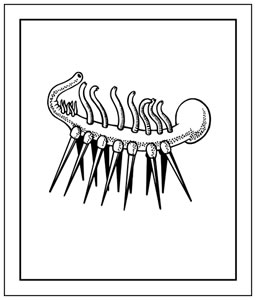

THE FIRST MULTI-CELLULAR CREATURES in the fossil record show up in rocks from about 530 million years ago. A dizzying variety of creatures appeared in a burst of evolutionary creativity known as the ‘Cambrian Explosion’. The plaque illustrates one of the strangest of these fossil creatures, Hallucigenia sparsa, which grew up three centimetres long.

THE FIRST MULTI-CELLULAR CREATURES in the fossil record show up in rocks from about 530 million years ago. A dizzying variety of creatures appeared in a burst of evolutionary creativity known as the ‘Cambrian Explosion’. The plaque illustrates one of the strangest of these fossil creatures, Hallucigenia sparsa, which grew up three centimetres long.

Most of the basic body forms or ‘phyla’ of animals evolved in the sea over a mere 50 million years or so, while the land surface remained completely bare. 160 million years later, the rocks of the Nagle Hills on the other side of river were laid down on what remained a largely desert continent, surrounded by an ocean teeming with fish. This period will be the subject of the next station, marked by a bronze fish in a boulder of sandstone.

This insight has led to a changed view of the evolution of higher animals. Starting with an evolutionary ‘Big Bang’ in the Cambrian, evolution proceeded rapidly, as species evolved to fill all the ecological niches created by each other. With all the niches filled, a period of stability followed. From then on, evolution has proceeded as a series of bursts of creativity following catastrophic extinctions.

Each extinction may actually reduce the number of phyla and genera, but leads to a radiation of the surviving genera to fill the available niches with new species. Extinctions have a variety of causes, the best known being the massive meteorite impact believed to have caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. In this model, the victims of extinctions are not the losers in a struggle for ‘the survival of the fittest’, in the classic Darwinian model, but are the victims of chance events. Competition is a vital factor in the radiation of survivors into newly available niches in the aftermath of extinctions.